Mariela Gemisheva works as an artist and fashion designer in Sofia, the city where she was born, in a society – that of Bulgaria – in which concepts such as glamour and fashion were alien for many years. And yet Mariela has turned this situation into an important opportunity to work on Fashion as an abstract concept, as pure expressive research, free of all prejudice. A world in which the final objective is not so much (or at least not only) the mass production and marketing of clothes. Her creations are in fact full critical analyses of the implicit codes of fashion and of its unspoken preconceptions.

Yet they always have all the wearability of “real” clothes, and indeed the artist has twice received the Golden Needle Award for avant-garde fashion from the Bulgarian Fashion Academy.

At the GAS Art Gallery, the artist is showing her Fashion Fire video installation, a performance put on in the courtyard of the Fire and Emergency Safety Service in Sofia.

The fashion show, which starts out as a normal parade of models on the catwalk (and the first model makes us think it will be no more than a routine show) gradually takes on a different overtone: with the same composure as during the show, and betraying only a slight indication of ironic maliciousness, they unveil themselves and throw their clothes (designed by Mariela) into the fire.

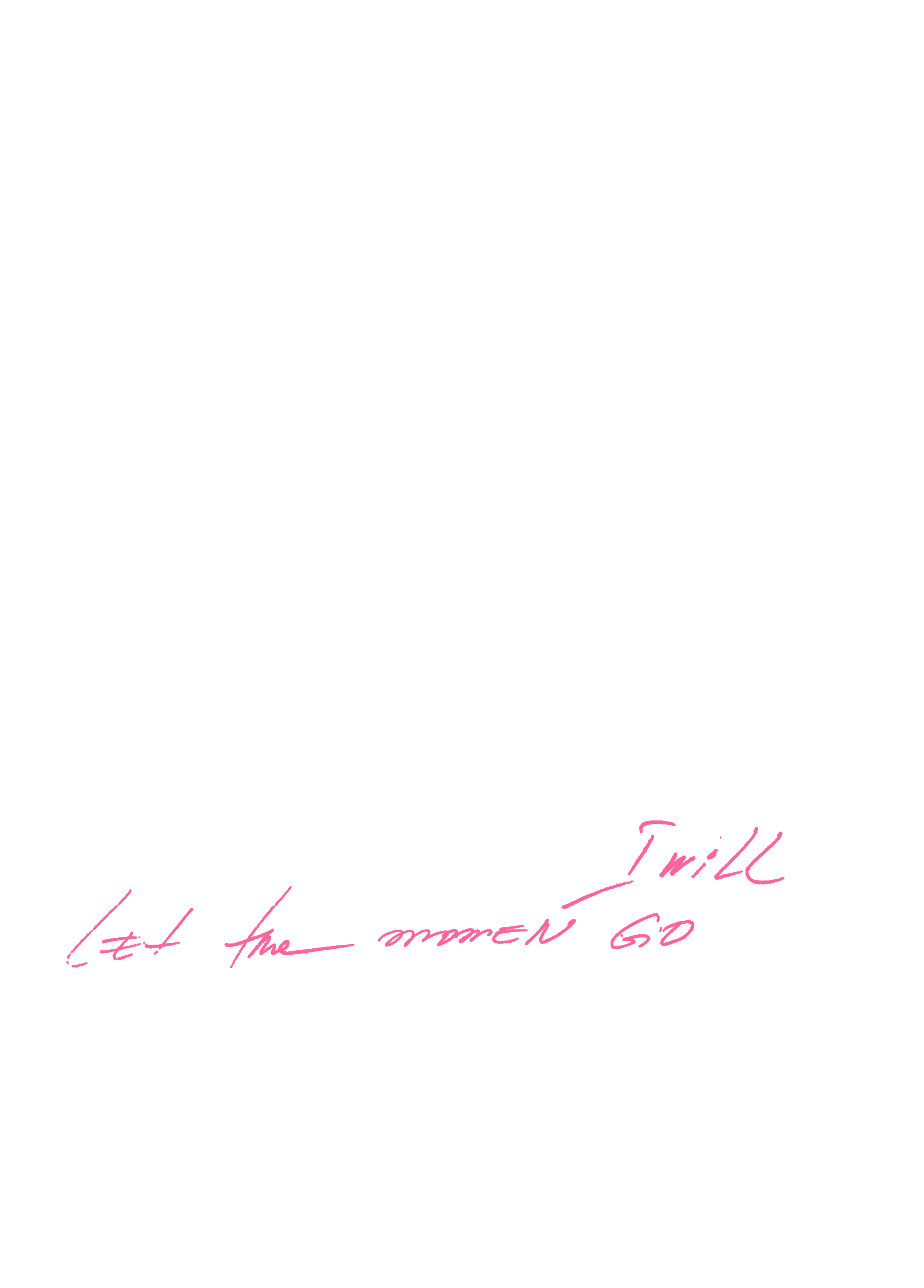

With this cathartic gesture, the artist focuses her attention – and the reference is clear in the subtitle of the video, The nice thing of one decent beauty queen – on the liberation of Fashion from the canons and unwritten rules that regulate its mechanisms.

In the intentions of the artist, the dress is no more than a supposition, a code to express the personality of the individual, a balanced compromise between freedom of and social conventions. When it no longer lives up to these premises, it is deprived of its function. For the artist, the garments in this collection, which are singularly romantic and coy, represent a model of womanhood that is now a thing of the past and yet still highly approved of by social codes: a model we must free ourselves from, both as a symbol and in practice.

From “art objects”, the models become “art subjects”, with their own autonomy – even as they carry out the will of the designer-artist – the young priestesses of a purifying rite: each one burns her dress as she personally deems fit.

Unlike Vanessa Beecroft’s feminine figures, which are dehumanised presences inspired by aestheticism and portrayed in aseptic, alienated poses, Mariela’s models express feelings of ironic rebellion and active refusal, by no means devoid of a certain dose of maliciousness. To some extent, they also regain possession of their femininity: they bashfully cover their breasts, so their nudity is not brazenly exhibited. In their act, played out to the sound of music, the ceremony of the fashion show takes place in reverse, accompanied by a conclusion that is equally symbolic and surreal: in the final appearance, when stepping out to the customary applause of the public, the designer burns the dress that had opened the parade. This is the most romantic and languorous – and the only one to have been initially spared – thus confirming the idea of a destructive yet liberating will. In her mock rescue by a fireman, it is herself that the artist ironically saves.

In the Out of Myself series of self-portraits, it is again the artist – in a shrewd realisation of her own ability to mutate – who bears witness to the infinite possibilities that Fashion. This is once again viewed as a potential means for expression that is free from regulations, conventions and rules imposed by society. A means that is conceded to the individual.

Elena Inchingolo

Paola Stropiana

GAS art gallery, Torino

Back to Fashion Fire (The Nice Thing of One Decent Beauty Quееn)