I have known Mariela Gemisheva for a long time and from a close distance – she is very determined and quick, straightforward and inventive, communicative and easy to make friends; and she knows how to get what she wants… A fashion designer and an artist, a PhD holder in art, a teacher and a lecturer, a “start-upper” and a business lady… She has won the Golden Needle, the highest award of the Bulgarian Fashion Academy – three times!

I do not know when exactly she decided to engage with fashion, provided her extensive designer’s education in the Prague Art Academy. This must have happened so naturally that I never even thought of asking. But I do recall clearly the not so distant time of the 1990s when this must have happened.

What was haute couture we only knew at the time from here say. It’s not that socialism did not develop a “fashion industry”; it’s just that it was stuck somewhere between the mass production and the limited edition product accessible only for a select few. Ultimately, both were a practice of rip offs from “western” models invested with various kinds of “capital” and quality control. It is a well known fact that clothing had a high symbolic value – from the blue jeans to the white fox fur collars. Except for some rare exceptions, to be fashionable meant to be like your group, community, and camp depending on the accessible consumers’ horizon – from the Central Department Store (ЦУМ) and the Center for New Goods and Fashion (ЦНСМ) all the way to the so called CoreCom – the hard currency exclusive free shops, whose abbreviated name from Comptoir de représentation et de commerce was quite logically deciphered as a “correction to communism” by the vernacular. And even the ‘bohemians’ – the male and female artists who were the societal elite at the time, had an unmistakable dress code. The former would not ware jackets but sweaters as a matter of principle, while the latter – hand-knitted colorful blouses and hand-painted silk scarves with massive silver jewelry, produced by the Craftsman’s Guild.

Then all of a sudden, along the political changes, there came consumerism and brought along the cheap Turkish-made clothes, the special-orders from abroad, the local fashion labels, the Bulgarian Fashion Academy and towards the end of the 1990s the Fashion Department in the National Art Academy in Sofia.

For a short time after graduating Mariela produced fashion lines of clothing – for the ever more demanding high school graduates as well as for the catwalks of the central hotels, theaters and clubs. The very world of these fashion demonstrations gave them a kind of ‘exclusivity’ and separation from life – lavish and somehow neutral dresses, clothing with a lot of hand-crafted detail that were not particularly appreciated by the global fashion trends at the time; as well as specific clothing for the then barely forming groups of business ladies, among others.

One of the first fashion collections of Mariela that I remember seeing around 1994 was based on the construction of the male shirt used in-principle for both females and males. Protracted down to the floor, with overly long sleeves that made it look like a priest’s habit, an 18th c. cape, a reduced frock-coat etc. and worn back-side to the front without either a collar or even without sleeves, the form of the shirt in Mariela’s hands turned out to be a Unisex symbol as this particular collection was called – accessible and fitting to everyone.

The Shirt but never the lady’s blouse, with its potential for variety, has remained in the ‘arsenal’ of Gemisheva, the designer, for a long time now. The shirt as a shroud – like in the show-performance Female interior accessories made for ONE DESIGN WEEK’2015 in Plovdiv; or often as a Victorian night-gown trying to be either a formal or a wedding dress; or even as a Space Suite for Angels (2011) for the ICA-Sofia exhibition dedicated to Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space.

The shirt might also be interpreted as either a trench coat or an overcoat as in, for example, the Guns and Roses oil – Edition 2 (2015) project for the customized-AK-47s holding “guardians” of the new symbol of the artist’s hometown – for centuries famous for its rose oil production, the city of Kazanluk is now notorious for its huge modernized gun factory. The shirt is transformed into a readable, non-binding attribute of modernization in her performance/spectacle/catwalk titled “The Great True Sawing” (2016) in the village of Bela Rechka, Bulgaria. The artist involved the ‘golden age’ local women in an engaging and attractive make-believe of a fashion show on a catwalk. She designed and saw person-specific dresses for each one of them, conducted multiple trials accompanied by sit-and-talk sessions; she put the elderly women through the hair stylist and the make-up expert; and finally the proud and emotionally rejuvenated ladies went on the ‘catwalk’ in front of their fellow villagers under the sounds of modern music.

There was a time when the seemingly simple formal male white shirt was Mariela’s most favorite clothing item. But we should point out that just like most artists dealing with cloths, she is not a ‘fashionista’ and she is not really, seriously after the trendy look. Indeed, the black color – minimal yet without fanaticism, together with a clearly visible element or an accessory from her favorite world famous designers, is always convenient and “fitting to most everything” that may cross the path of the modern dynamic lady in her everyday life. However, the taste for and in fashions, for the aroma and the accessories, for the coiffure, the make-up and styling, for ‘playing the part of the other’ is usually visible in the photographic oeuvre of the artist. That applies for both her marketing images – magazines, websites and portals, as well as for her special projects based on photography.

In her first photo installation Mariela was not present herself. Spring – Summer – Autumn – Winter (2001) is dedicated to visualizing the ‘origins and genesis’ of the artist – her mother,Mrs. Donka Gemisheva .This work consists of a series of full-figure portraits of her mother, wearing specially self-selected dresses. The photographs were taken in an ordinary photographic studio in their home town of Kazanluk. On one side this project celebrated the special taste and attention to detail displayed by the author of the dresses in those portraits; but on the other, the set of images is a unique testimony to clothing in out-of-the-capital Bulgaria in the years after the political changes of 1989. It is also a witness to the dreams and the possibilities, to nostalgia as well as to the new openness for the rest of the world. The cycle of photographs represents a grand lady-dandy always wearing a minutely stylized post-modern color schemes combined with carefully selected accessories especially hats and shoes. Her personal predilections as well as her tight and imposing attitude are somehow reminiscent of Elisabeth II, the British Queen, whose personal style has long been the target of media attention and sometime ridicule to only be recognized for what it is ultimately – an expression of the unique individuality of a strong and liberated person.

Following on the footsteps of this somewhat arrogant dandyism is the photographic cycle titled Out of Myself (2002) where the mischievous Gemisheva is alternatively the naïve ‘loving child’ dressed in a veiled black-and-white dress of dots and stripes; then the dominatrix in a tight corset holding Paris’ apple against her red-painted lips. Or she mutates into the playful ingénue who is lifting up her first ball dress; and yet she might appear to be an office clerc dressed up in purple for the office party just like the one described by O. Henry in his The Purple Dress. Furthermore, she might transform into a monument to the tormented yet all-overpowering femininity dressed up in a white bloodied dress with a huge cut-off fish head in her hands, positioned where otherwise the notorious crushed flower would be seen. One might read in this cycle a hint for the portfolio of a professional model that is forced by the market to display her bodily and other abilities; but also this is a clearly enjoyed by the author ironical take on fashion – here a mask, a code, a signifier and an equalizer.

We should stress the fact that, as the not-so-sophisticated journals for ladies might put it – the foundation for the Mariela Gemisheva kind of fashion is “her majesty the dress”. The dress as in that piece of clothing, which according to the seamstress’s understanding is based on the shoulders and for centuries has signified the female no matter how many exceptions there are to this kind of restriction. On one hand, Mariela’s are most often the obvious “dresses” – cocoons, wrappings hiding the body; puffed up, multilayered, rumpled, made out of seemingly precious materials. On the other – with all her work the artist-designer has been waging a war on the dress. The fashion performance My wedding dress on the roof (1998) is incredibly important in its symbolism work. The wedding dresses – white and tender symbols of purity in all of its perceived meanings, are crumpled, cut off, their seams are reversed, the elements are switched, and the details are half-torn or even removed. The ‘wedding-ness’ as a whole with its ritualistic ceremonial nature has been canceled here for the benefit of some unashamed bacchanal feast that is opposing the female sacrifice, ingrained in the wedding ritual. In 2006 those wedding dresses were repurposed into a floor carpet, the Ladies Carpet, which you can walk on with your shoes on…

In order to get rid of them the artist even sent the dresses to “burn in hell” – publically and spectacularly under the sounds of drumming, she put them to the stake (Fashion Fire, 2003) thus demonstrating her perfect sense for effect and show-woman-ship. As Miuccia Prada says: “You want to be understood by the sophisticated few but you also have to be more loud somehow, otherwise your message doesn't go through.”

In another one of her photographic series titled Self-portrait (2008), the battle with the dress (the wedding one, by default) acquired private undertones. The artist puts it on, rearranges it, shows it off for a moment and then frees herself from this cocoon allegro agitato: she tears it apart, she rips it up, and she is almost hysterically lacerating it. Then she puts on a black dress in an adagio dishabille tempo. That is how an incredible statement on the fragility of the conventionally beautiful is born.

Here I would like to precede a question usually asked by those unfamiliar with contemporary art – Mariela is fluent in traditional dress making for wear! Many times I have dreamed about this or that of her dresses while observing how those take off in her magna war waged on the clichéd femininity… The dress revisits, for example, as a ‘dress/an elegant evening uniform’ in her experimental work Multi- Me (2012) where the charming models, dressed in identical clothing, are transformed into some kind of a female mini-army on high hills (Regards to Helmut Newton!) The artist herself is in a similar yet plastically wealthier dress of a deconstructive design and shapes reminiscent of a sculpted drapery. Once again she is the model for her own designs doubled up via the photograph. Is the designer’s dress here a kind of an equalizer? Is this the fashion designer who visually remembers the dystopian samples of socialism and is presenting them here realized with a weird perverse pleasure?

As it turned out Mariela Gemisheva found a fresh application for her dress-as-a-uniform idea – the stage costumes and at the same time accessories for an orgiastic dance spectacle for the students at the Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburg, USA. With their movements they get rid of the cocoon in a body revolt of immense visual power.

The torn dress disrobes the body but it also reveals the underwear. That part of the female clothing is one of the central elements of Mariela Gemisheva’s work. Having grown in socialist Bulgaria, she does have the memory as well as the intuition for the specific place occupied by the intimate sphere within the larger society – suppressed to the level of denial and strictly controlled through the complex notion of shame. In socialist times a lot of things in life were made to look shameful and one of those was to see underwear in public… So, there you go, in 1996 Gemisheva showed not only the underwear in an almost traditional fashion collection titled Experiment 2, but she also placed it on top of other clothing which was red in color and male if gender and also the kind worn by male strippers!

Our first artist-curator collaboration was within the ‘revisionist’ exhibition project “Erato’s Version” (1997, co-curated with Maria Vassileva), which was initiated by Bulgarian female artists enraged with the fact that locally the theme of erotica in art is mainly left to the “mighty” hands of male artists alone. The idea behind this quite early for our scene political and gender-aware exhibition was to manifest the female notion of erotica. It was no surprise that this notion turned out to be socially and politically tinted. For this show Mariela Gemisheva presented a performance that was most obviously rooted in a sexist joke. The joke relates the story of a blind man passing by a fish market. While confusing the smells from the surroundings he is offering the mischievous greeting: “Hi, girls!” The performance consisted of a beautiful young girl dressed in sexy underwear, positioned under a laced baldachin, frying cheap and smelly fish on a hot plate. This was a situation so shocking for the audience that they did not know what to make of the work. An additionally ironical/erotic element was the metal structure/construction worn by the lady performer, which reminded the audience of the medieval chastity belts. Later on the same performance was recast in the numerous Fish Parties (2004, 2012 and 2015) where the conditional signs of chastity – the white dresses worn in some cases by models and in others – by a charming male model; and at the end by Mariela herself, were radically contradicted by the smell and the usual dirt surrounding the fish frying procedure.

Overcoming “collective shame” related to the intimate sphere is deeply ingrained within the attractive-repulsive game that Mariela Gemisheva has been playing with the boudoir. This is visible in many projects among which the most revealing for the author herself is the Peep Show – an easy going endurance performance which is demolishing the boundary between the public and the private. During the Night of Museums and Galleries in Plovdiv the artist was disrobing slowly and elegantly down to her underwear in front of the viewers on the street. Then she was theatrically going for a sleep on a bed made out of her lavish cloak. The comments from the viewers came in the form of red-lipstick kisses left on the glass vitrine separating them from the author who was sleeping inside the gallery space.

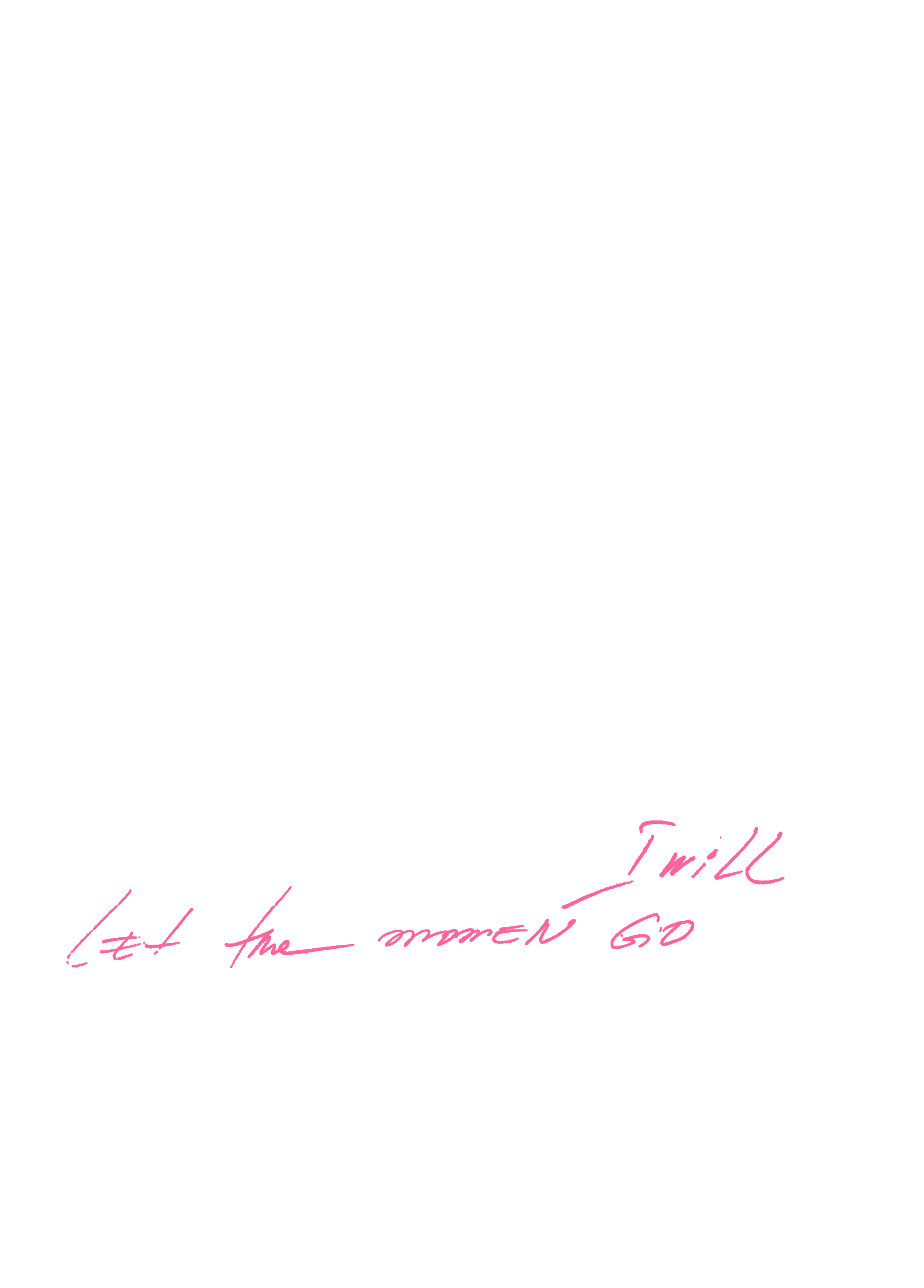

The sheer volume and saturation of the issues and questions that Mariela Gemisheva is dealing with position her work as an energetic and constant corrective on our notion for what fashion might be within the wide open range between a profitable business and a limitless field of creativity.

Iara Boubnova